Amazon, the monster warehouse and retailer that now employs 716,500 U.S. workers, likes to tout itself as “an industry leader” for the rest of the country. Two new reports and an ongoing case in Washington State show it is—in worker pain, injuries and suffering.

And of course, as Washington State pointed out in its latest citation and fine against the behemoth for on-the-job injuries, this time in Spokane, Amazon has both the wealth—owner Jeff Bezos is one of the world’s richest people—and know-how to prevent such evils, but doesn’t.

It also certainly has the cash, even without Bezos at the helm anymore: Amazon’s profits for calendar year 2022 totaled more than $225 billion, a 14% increase from 2021. Its profit for that year was $197.5 billion, a 29.28% increase from 2020.

The reports, one based on years’ worth of federal job safety and health citations and the other on a comprehensive survey among Amazon warehouse workers nationwide, paint a bleak picture of conditions at Amazon warehouses, which it calls “fulfillment centers.” So does the Washington State case.

Bluntly, 41% of the 1,484 Amazon warehouse workers toiling in 42 states suffered musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs)—ergonomic injuries, in plain English—according to the most recent study, from the University of Illinois at Chicago. And according to that study, released in October, 51% of Amazon workers who’ve toiled for the firm at least three years were hurt by MSDs.

Ergonomic injuries were a key talking point for the independent Amazon Labor Union when it tried to organize the firm’s warehouse just south of Albany, New York, and in its current campaign to organize a warehouse near Ontario Airport in Los Angeles. Amazon labor law-breaking defeated the Albany effort, and ALU is appealing its election loss.

ALU began, and eventually handily won, a National Labor Relations Board recognition election at Amazon’s JFK8 warehouse on Staten Island, New York, over another health hazard: Amazon’s failure to protect—or even inform—workers there about coronavirus exposure on the job.

The university’s report, "Pain Points: Data on Work Intensity, Monitoring and Health at Amazon," added that 69% had to take unpaid time off in the past month “due to pain or exhaustion” from work at Amazon, and a third had to do so at least three times.

More than half of the Amazon warehouse workers surveyed (52%) said they felt “burned out.” The burned-out share rises to 60% among the three-year-plus veterans. The burnout comes from Amazon’s demanding workplace, with 71% feeling “a sense of pressure to work faster always, most or some of the time.”

Amazon keeps track of what it calls “time off task” via monitoring of individual workers, docking them for everything from taking too long to go to the bathroom in its football-stadium-sized warehouses to—in one horrifying case—cordoning off and covering up a death on the job in December at its Colorado Springs, Colorado, warehouse.

The Guardian reported Rick Jacobs, 61, collapsed and died of “a cardiac event” on the warehouse’s outboard shipping dock. Outraged workers later told the paper bosses surrounded the body with cardboard bins so incoming workers wouldn’t see it.

They also didn’t tell workers arriving for the next shift what had happened, much less arranged for any workers to go home, see counselors, or both. Instead, the bosses guarded Jacobs’ “boxed” body while waiting for the coroner to arrive. Jacobs’ death was not in the University of Illinois report, which dealt with on-the-job injuries causing workers to miss time.

“Finding out what had happened after walking through there had made me feel very uncomfortable, as there is a blatant disregard of human emotions at this facility. Management could have released those employees affected by offering [voluntary time off], so that they did not need to use their own time, but nope, that did not happen,” one worker who remained anonymous to avoid company retribution, told the paper.

Before that, National Council for Occupational Safety and Health (NACOSH) reported in Dirty Dozen this year that “Amazon worker Rafael Reynaldo Mota Frias, 42, died from cardiac arrest at an Amazon warehouse in Carteret, N.J., on July 13, 2022. It was ‘Prime Day,’ a high-pressure sales event for Amazon. Co-workers told The Daily Beast the facility does not have air conditioning in its main work area.”

“It is concerning most Amazon warehouse workers need to take unpaid time off due to pain or exhaustion as a kind of tacit condition of working at the company,” University of Illinois-Chicago report co-author Dr. Sanjay Pinto said in a statement. “This reduces workers’ paychecks in the immediate term. The magnitude of the health toll should also raise concerns about potential long-term effects on well-being, medical costs, future employment, and overall economic security.

“A large share of people laboring in Amazon warehouses are suffering from having worked there, with many reporting pain and injury as well as burnout and other forms of psychosocial stress," Pinto said. "Amazon has been heralded as a quintessential ‘innovator,’ reshaping norms and practices in warehousing and the economy more broadly. Our survey data suggest its drive towards ever-greater speed and efficiency carries significant costs being displaced onto its workforce.”

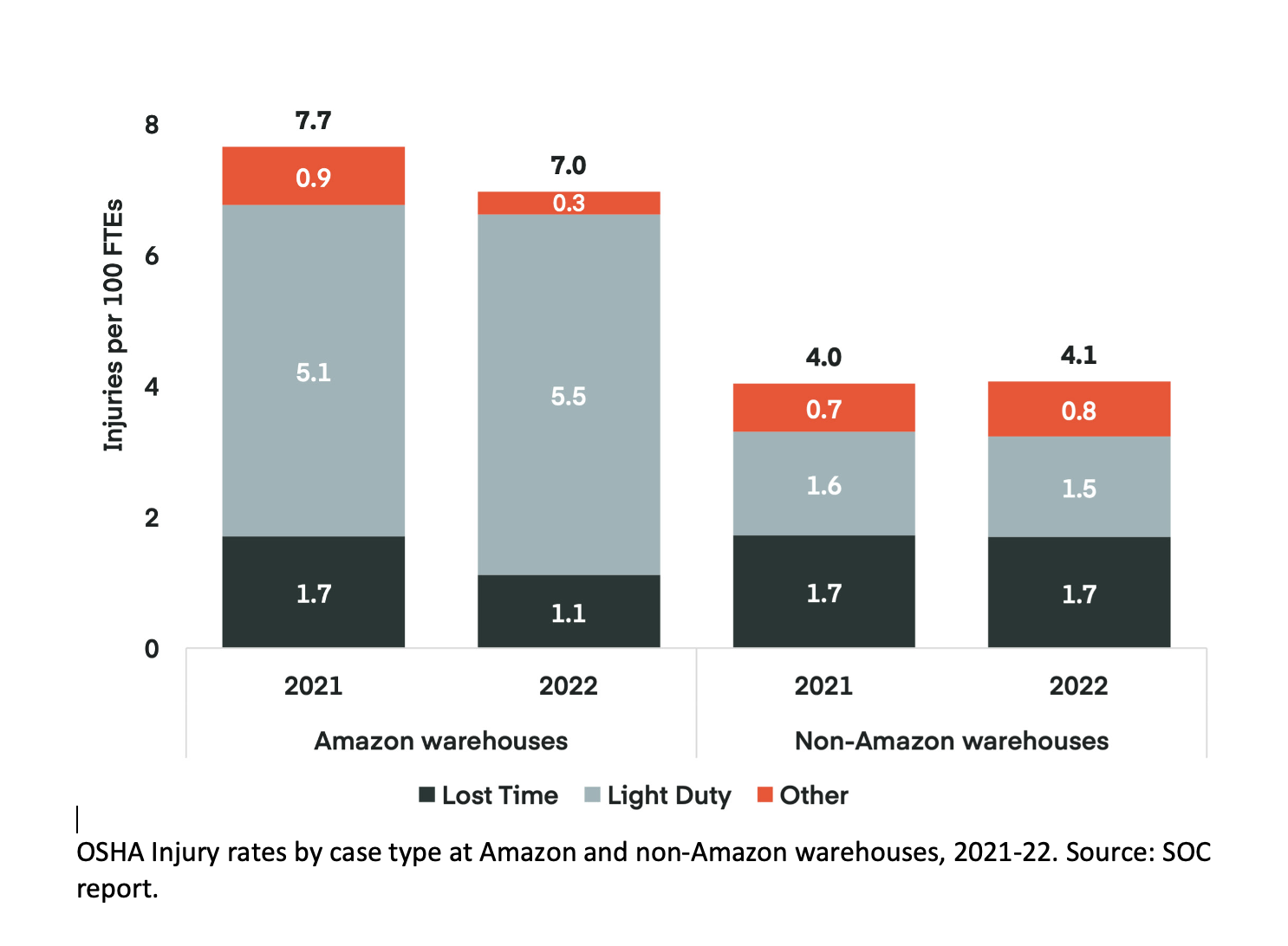

The prior report, "Denial: Amazon’s Continuing Failure to Fix Its Injury Crisis," examined Occupational Safety and Health Administration records for Amazon from 2017–22. It found Amazon with on-the-job injury rates leading all warehouse firms in the United States, with yearly injury rates 50% above those of its peers.

The only time the numbers edged downward was during the first six months of the coronavirus pandemic, when Amazon had to both send sick workers home for quarantine and reduce its line speeds because so many were out ill, said the report by the Strategic Opportunities Center, a joint Communications Workers–Service Employees–United Farm Workers institute.

That report cited the Washington State Amazon investigation, too. The state’s probers, SOC said, revealed “Amazon is demonstrating plain indifference” to injuries on the job. “They have been made aware of the hazards and increased injury rates yet are making no effort to take corrective action. In stark contrast to these findings by OSHA investigators, Amazon’s executives continued to deny the company’s production quotas pose a risk to worker safety."

The Amazon job injury problem was acute, particularly last year, the SOC report says.

“In 2022, there were 38,609 total recordable injuries—those requiring medical treatment beyond first aid or requiring time off a worker’s regular job—at Amazon facilities. The vast majority were serious: 36,487, or 95%,” and either forced the firm to put injured workers on light duty or forced them to take time off to recuperate.

That actually understates the severity of the injuries to Amazon warehouse workers, the report added. Some 37% of workers assigned to “light duty” after they were injured were pressured to return to work before they had healed, they told the institute’s probers.

In 2017, three-fourths of injured Amazon workers lost time from their jobs while the other fourth were put on light duty, the report shows. By 2022, those proportions exactly reversed. Forcing workers onto light duty, early or not, let Amazon cut its workers’ comp costs by 70%, one company executive calculated.

The real cost, of course, is to the workers’ health and ability to work, at the warehouse or in the future.

“Amazon’s response to heightened scrutiny of its safety record has been to resist accountability for its failures and to use cherry-picked data to mislead the public,” the report says. That reduction in workers’ comp costs was one statistic in the cherry-picked data, it noted.

“Amazon invested $1 billion from 2019–22 in safety initiatives, but with no discernible impact," the report noted. "The company has failed to even match its own performance from two years earlier, and has not come close to parity with its warehouse industry peers.

“For a corporation that prides itself on moving quickly and decisively informed by sophisticated data analysis, Amazon’s ongoing failure to provide safe working conditions raises major questions about whether the company’s management is serious” about safety “or whether it continues to put profits before the safety of the very people responsible for its success.”